Four weeks have passed, and I feel like I have no stories to tell. This setting has become normal – the cycle ride to work, the medical ward rounds, the meetings, volleyball on Saturdays. Children come and go, they get better or die, and one ceases to notice or apply significance to the deaths as this is all in a days work, and beyond today that child only exists in the monthly statistics. Is this the start of the inevitable descent into jadedness, the pragmatic distancing of oneself from an uncomfortable reality? Or a reasonable appreciation of a situation that has become quotidian? Am I not really asking: am I well, am I happy, is my world all right or does it need to change?

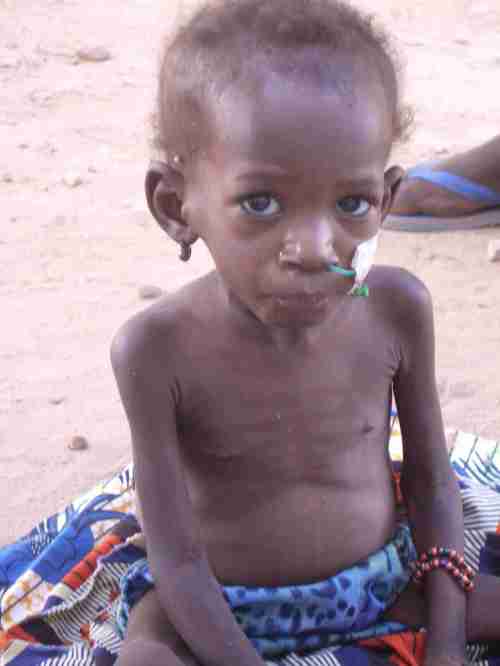

Yet if I search I can recall the characters that constitute my recent existence. The tiny but beautifully made-up girl who has been in the hospital for weeks stares out at you through her feverish and bewildered eyes, trying to make sense of what you (and the world) are doing to her. One day I find her hanging off the edge of the bed, crying, wishing to escape but too terrified to drop to the floor. Her mother, who is also sick, has gone to the hospital. As I put her back on the bed she screams and screams at me – what are you doing to me? You think you are trying to help, but how can you possibly know what I want, what I need? Around us the patients and their mothers are tired, confused, sometimes contented, often upset and disappointed. There are definitely more tears than laughter here. Can we really feel confident that our work is bringing benefit?

I spend my days trying to motivate, trying to instruct, but also trying to supervise which means using both the carrot and the stick. At some moments my presence just feels combatitive and disruptive – I suppose if you are the one leading the service, you have to accept a degree of uncertainty about the validity and efficacy of your actions. You have to maintain faith in your effectiveness, somehow. I guess, for me, this comes from tiny moments in the day, brief encounters. An occasional cry of delight from a mother when she learns that her child is ready for release. The warm handshake from a father, when, against all odds, his malnourished son recovers from a state of septic shock. And even in the meetings, when the staff laugh as they agree to take on more work. Flimsy indicators for the success of ones work, but at some level they mean much more to us than the monthly mortality rate.

Keep looking at the small and sometimes what seems insignificant details. It’s hard sometimes where-ever we work as GP’s to see the benefit of what we do (amongst the relentless nature of the streams of patients), but what we perhaps do best is to be a presence and part of people’s lives and communities, the good and the bad. It seems that’s what you’re doing. But it’s not easy.